©2001 Terry Gruber

The Virginia Regiment Uniform 1754-62

The provincial forces of Virginia during the French and Indian War era developed a reputation among the British regular army as an effective and well-appointed military force. The impressive military appearance can be attributed to the military ambitions of its primary influence in its formative years, George Washington. Having failed to gain a commission in the regular army, Washington, as commander of the Virginia Regiment in August of 1755, set out to make his army in everyway the emulation and equal of the professionals of George II. He began the task by regulating the appearance of the troops.

This paper will look at the uniform from the very beginning of the regiment in 1754 (the failed Fort Necessity campaign) and attempt to document the changes made to the uniform through the war years to the regiment’s disbandment in 1762. Because Washington meticulously documented his activities during this period, what is known about the regiment and its equipment comes from the earliest years of the regiment until Washington’s resignation at the end of the successful Fort Duquesne campaign in the waning days of 1758. It is hoped that the information herein may be of assistance to those attempting to recreate the uniform of the regiment, either materially or visually.

As yet, any orders for the making of uniforms, if they exist, have not been found. Evidence has been found in various collections of letters that give hints about the color and elements of the uniform. But there are no descriptions of the style. Single and double breasted coats were used for regimentals, with the single breasted style being used more frequently by provincial troops. There is no conclusive evidence relating to any of the possible style elements of the period. Consequently, convention and known personal biases of those ordering the uniform must be taken into account.

Without any detailed description of the uniform (such as an order made in London), a variety of creative methods must be used in order to arrive at a best guess for the appearance of the Virginia troops. Whenever there is no documentation for uniform style and equipment, it is believed that the safest conjecture is to rely on what was conventional for the day. Personal biases of the leaders can also be taken into account. Washington was very concerned that his troops would be the equal of the British counterparts. Appearance would be the starting point. Therefore the style of the regimental, hats, waistcoats, shoes, and accoutrements are assumed to be standard British military style. From the numerous necessary rolls that exist in Washington’s papers that specifically mention these elements, it is known that the regiment wore these basic elements of military clothing. It is not known, nor can be known, what kinds of buttons were used, style of shoe buckles and other types of buckles, etc. In such a case, it is probably safe to use what a military force usually wore. Even then, there could be great variability. Only archaeology conducted at a site that was exclusively used by the Virginia Regiment may provide evidence for these details.

The Uniforms

The first uniform for the regiment was conceived of as almost an afterthought while the newly formed regiment was recruiting and collecting provisions for its first campaign to oust the French from the Forks of the Ohio in 1754. In March, Washington remarked upon the poor state of clothing for the regiment and requested Dinwiddie to provide a uniform for the soldiers (Brock, v.1, 92). Later in the month a uniform consisting of "a Coat and Breeches of red Cloth" (Brock, v.1, 116) was decided upon. However, it seems that not enough uniforms were obtained on such short notice, because as late as June 28 (Washington surrendered at Fort Necessity on July 3) uniforms were still being sent from Alexandria (Abbot v.1, 153-54). Therefore only part of the regiment wore the red coat, while many of the rest had checked shirts, and apparently the pants in which they arrived to the service (Abbot, v.1, 141). In a 1757 letter to the new commander of British forces in America, Lord Loudoun, Washington stated that "the first Twelve Months of their [the soldiers] Service they received no clothing" (Abbot, v.4, 86). Washington’s comment indicates that the regiment had no real uniform in 1754.

Therefore it appears that the real first uniform followed the color scheme of blue with red facings; a scheme that was followed for the regiment’s entire existence. This uniform was ordered and purchased in London through John Hanbury in the fall of 1754 and arrived in March of 1755, in time for the regiment to leave Will’s Creek (Fort Cumberland) with General Edward Braddock on the ill-fated Fort Duquesne campaign. In spite of no order for the making of the uniforms having yet been found, there are a couple of hints that lead to a conclusion that this first uniform was blue. One, is a reference of Captain Robert Orme’s, in a description of the Battle of the Monongahela, to the "Virginia blues". The other reference is in a letter from Governor Dinwiddie to Captain Robert Stewart on 26 November 1754 advising him to purchase "some cheap blue Clothing" for his men while they await the arrival of the uniforms from Britain (Brock, v.1, 413). The quality of this first uniform seems to have been something less than the expectations for a standard uniform, for Washington described this uniform to Lord Loudoun as "a suit of thin sleazy Cloth without lining, and without Waistcoats except of sorry Flannel" (Abbot, v.4, 86).

When the Regiment was reorganized after the Braddock campaign with Washington as its colonel, the first orders concerning the uniform are extant. The regimental is ordered blue with red facings, a red waistcoat, and blue breeches. However, approximately one and one-half years would pass before the soldiers received their uniforms from London. The timing was fortuitous because they arrived just as several companies were to leave for Charles Town, South Carolina to act in conjunction with the British. These uniforms were apparently impressive to the British officers because the Virginia officers received several compliments on the appearance and bearing of their soldiers (Abbot, v.4, 373).

It appears that the regiment was kept in good uniforms for the remainder of their service, except during the 1758 Fort Duquesne campaign. Because their old uniforms were literally worn out, and the new ones had not arrived from England, the regiment was authorized by General John Forbes to wear Indian clothing (hunting shirts, breechcloths, and wool leggings) for the campaign. The new uniforms arrived before the end of the campaign, just as the colder fall weather was setting in. Deserter notices describing the regimental as late as May 1762 advertise a deserter having "a blue Coat, turnup with red", thus making it likely that the regiment used the red on blue color scheme from 1754 to 1762 (Pennsylvania Gazette, 29 July 1762).

The Uniforms’ Appearance

It is no easy task to determine the probable appearance of the Virginia Regiment uniform. We know the color scheme, but not the style. Therefore, relying on standard military styling appears to be the safest conjecture, however this period was a transition period for the British army. There were several styles of gaiters, waistcoat tail lengths were changing, and more earth-toned colors for uniforms were being experimented with. Fortunately, Washington kept wonderfully meticulous records that can provide enough information to make very probable conjectures concerning the uniform of the Virginia forces. The red "uniform" may have been a single breasted coat or jacket. The following discussion relates to the first bonafide uniform that was manufactured in England.

Further discussion will be conducted below using contemporary paintings and drawings:

Figure

1 The picture to the left is of a private in the 44th

Regiment of Foot drawn in 1742. This picture illustrates the older style of

uniform used by the British at the outset of the French and Indian War. Note the

cuffs are simple long cuffs that are rolled up, revealing the facing color of

the regiment. Also note the "V" or "U" cut on the cuff and

the buttoned flap in the cut. Pictures below will illustrate the variability of

the cuff cuts. There is a linen neckstock and the regimental has no collar. Note

the waistbelt and double frog with both the bayonet and a hanger (sword). The

sword was not issued to private men by the time of the French and Indian War

except to the grenadiers. Sergeants continued to be issued the hangers. This

soldier is wearing the cartridge pouch on his right side. The gaiters appear

slightly shorter than other contemporary illustrations. By the time of the 1750’s

and 1760’s, the gaiter had several possibilities. Note, too, the length of the

waistcoat tails coming down to nearly mid-thigh. Note the length of the

waistcoat tails on the 1770 painting of George Washington below; the length of

the tails was rising from the 1740’s to 1770’s. Also note the white hat lace

and cockade, as well as the off-center angle of the hat (to not interfere with

the firelock when it is shouldered). This position was regulated, requiring the

hat to be "cocked", meaning tilted upward away from the left side. The

waistbelt worn on the outside of the regimental appears to have dropped from

vogue by the 1750’s, except when the regimental is buttoned. Many of the style

elements of this uniform remain the same during the French and Indian War. Some

of the equipment changed however.

Figure

1 The picture to the left is of a private in the 44th

Regiment of Foot drawn in 1742. This picture illustrates the older style of

uniform used by the British at the outset of the French and Indian War. Note the

cuffs are simple long cuffs that are rolled up, revealing the facing color of

the regiment. Also note the "V" or "U" cut on the cuff and

the buttoned flap in the cut. Pictures below will illustrate the variability of

the cuff cuts. There is a linen neckstock and the regimental has no collar. Note

the waistbelt and double frog with both the bayonet and a hanger (sword). The

sword was not issued to private men by the time of the French and Indian War

except to the grenadiers. Sergeants continued to be issued the hangers. This

soldier is wearing the cartridge pouch on his right side. The gaiters appear

slightly shorter than other contemporary illustrations. By the time of the 1750’s

and 1760’s, the gaiter had several possibilities. Note, too, the length of the

waistcoat tails coming down to nearly mid-thigh. Note the length of the

waistcoat tails on the 1770 painting of George Washington below; the length of

the tails was rising from the 1740’s to 1770’s. Also note the white hat lace

and cockade, as well as the off-center angle of the hat (to not interfere with

the firelock when it is shouldered). This position was regulated, requiring the

hat to be "cocked", meaning tilted upward away from the left side. The

waistbelt worn on the outside of the regimental appears to have dropped from

vogue by the 1750’s, except when the regimental is buttoned. Many of the style

elements of this uniform remain the same during the French and Indian War. Some

of the equipment changed however.

In September 1755, Washington ordered every officer:

…to provide himself as soon as he can conveniently, with a Suit of Regimentals of good blue Cloath, the Coat to be faced and cuffed with Scarlet, and trimmed with Silver: a Scarlet waistcoat, with silver lace, blue Breeches, and a silver-laced Hat, if to be had for Camp or Garrison Duty. Besides this, each Officer to provide himself with a common Soldiers Dress, for Detachments, and Duty in the Woods. (Abbot, v.2, 41)

The common soldiers’ dress mentioned by Washington probably substituted Madder Red for the Scarlet and had no lace (lace being an added expense to the uniform as well as time-consuming to make the special order regimental lace). The Royal American Regiment is a contemporary example of a regiment that had no regimental lace. The colony would provide the soldiers with their uniforms and keep a small portion of the soldiers’ pay over a period of time in order to pay for the uniform.

Figure 2 This painting is one of an extensive series of paintings commissioned of David Morier by the Duke of Cumberland in 1751. Note the slightly shorter waistcoat tails and the variations of the cut of the cuff ("U" and "V" shaped). The 3-button flap is still positioned on the sleeve as the above picture. The uniform and equipment is essentially the same as its counterpart of 1742. Because these are soldiers of a special nature (grenadiers), there are some equipment and uniform details that would not be seen on common foot soldiers. The shoulder flaps at the top of the sleeves and hanger are exclusive elements of grenadiers. This painting is a good representation of equipment as it was carried on the march. Note the canteen on the right figure (a type found frequently in various archaeological excavations), haversack on the left figure and the cartridge box on the center figure (small , black box suspended at the waist in the front).

The painting above was painted just three years prior to the opening engagement of the war. The uniform would, in all likelihood, be very close in style to these examples, except perhaps the gaiters.

Gaiter style is one of

the most difficult questions to answer, since during this period there were

several styles of gaiters and no descriptions of what the regiment wore. There

are only two refernces to leg coverings: the first in a letter of July 1754

(Brock, v.1, 238,41) and the other in a regimental administrative paper of

October 1758 (Regimental Necessary Roll, GW Papers). Both references identify

"spatterdashes" being worn or needed by the regiment. Consulting

dictionaries has not yielded a definition of "spatterdashes", however

the author has questioned several individuals knowledgeable in military matters

of this period. They have stated that the spatterdashes were the newer style

gaiter (also "half-gaiters) that rose to the knee and was topped with a

leather knee protective cap. Confusing things, however is the consistent mention

in necessary rolls of "garters and buckles". It is not yet known if

these were routinely issued by the military for the soldiers stockings or were

they the type of garter designed to hold up the over-the-knee type of gaiter.

The author suspects the garters and buckles probably  refer

to devices for holding up the stockings.

refer

to devices for holding up the stockings.

Figure 3 This soldier, drawn by Lieutenant William Baille in 1753, is a member of a recruiting party of the 13th Regiment in Birmingham, England. Again, note very little difference in style from the 1751 and 1742 pictures above. Note the cuffs and hook and eye attaching the flaps of the regimental coat. Note the cocked hat (tilting away from the left shoulder). This soldier has a hanger at his waist.

It is probable that the style of the early Virginia Regiment uniform would have been very similar to the uniforms thus far presented. During the 1760’s the uniform may have taken on a different look, though still not radically different. Perhaps the most notable difference would have been slightly shorter waistcoat tails and a hat with a peaked front closer in appearance to a bicorn rather than a tricorn hat.

|

|

Figure 4 (left) and 5 (above) These two sketches were drawn around 1760 by Sandby. The gaiters on the left are " spatterdashes" or "half-gaiters". Above are depicted the other of the newer style gaiter that rises to just over the knee. Notice the peaked hat instead of a tricorn. It seems that by 1760, the half-gaiter was quite common. An article in the the Annual Register mentioned that a ladies support group was making 6000 pair of "half-gaiters" for troops in North America and Germany (Annual Register, v. 3, 67). |

|

Figure 6 This portrait of George Washington was painted in 1772 by Charles Wilson Peale. He is likely dressed in the uniform of an officer of his county militia. The short waistcoat tails clearly identify this portrait as being painted sometime around or after 1770. Note the cuff; this cuff was common by the 1750’s on naval officer’s uniforms and was beginning to be adopted by army officers. Also note the very small collar on the regimental. This uniform is similar in color to that worn by Virginia regimental officers during the French and Indian War. The blue might have been the lighter blue seen in the highlights. |

Figure 7 This detail from a contemporary woodcut depicting Colonel Henry Bouquet negotiating with the Ohio Indians (during the Royal American Regiment’s expedition to the Muskingham region in 1764) shows the officers’ uniform cuff in transition. Bouquet, on the left, has the new naval officers’ cuff, while the officer to the right exhibits the old rolled cuff. Note this same officer’s double-breasted waistcoat. It appears that Bouquet preferred the old fashioned high gaiter. |

The Necessary Rolls

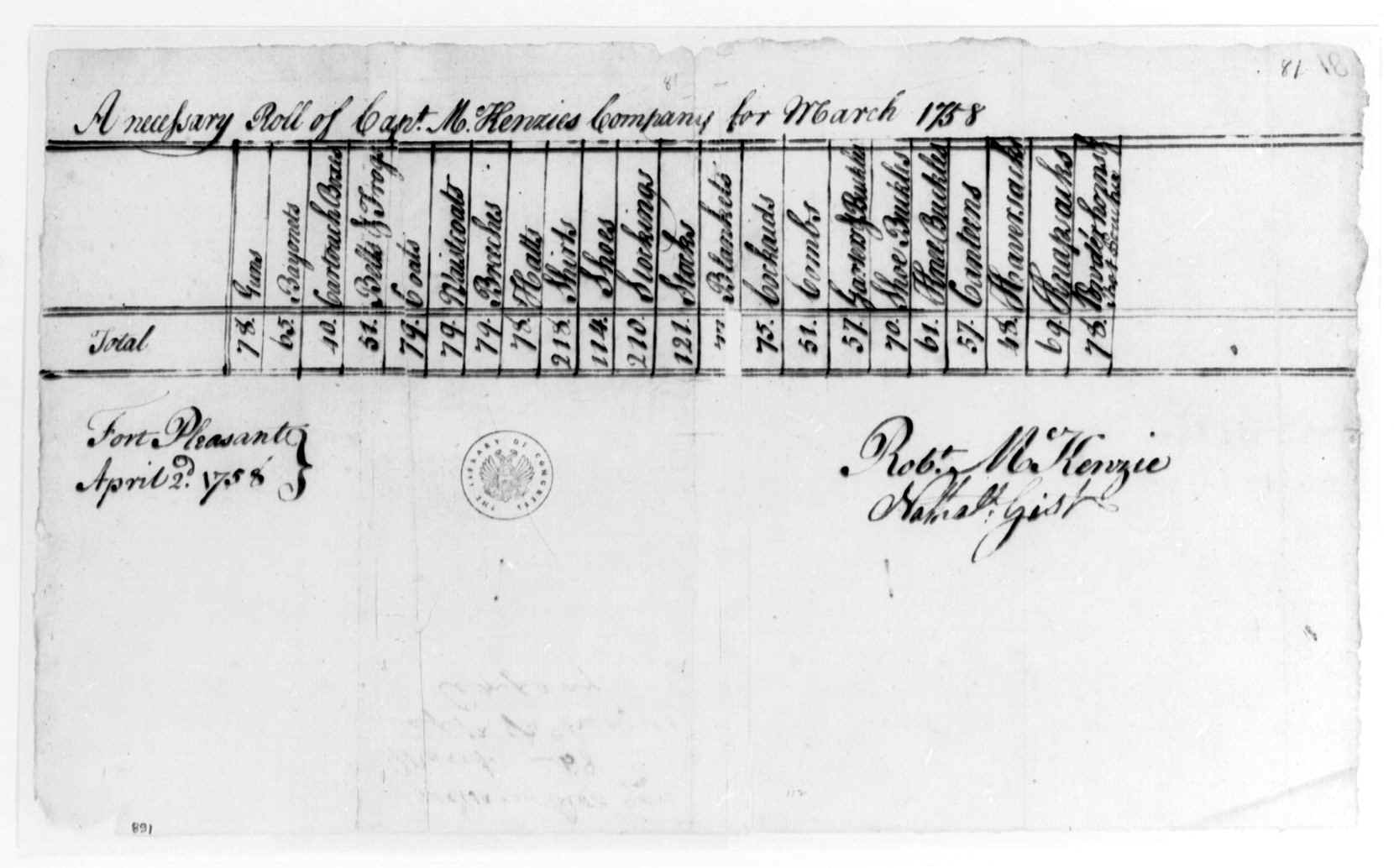

Valuable documents to the determination of clothing quantities issued and accoutrements possessed are the various necessary rolls preserved in Washington’s papers. Necessary rolls were requested by Washington of his officers on a monthly basis. Most of the rolls list the name of each individual in the company and the equipment each had. From these lists, it could be determined what clothing and equipment was needed by the company. There is one necessary roll that lists equipment for each of the companies of the entire regiment. There are items on this list that do not appear on any of the other lists: jackets, tents (this roll was taken during the 1758 Fort Duquesne campaign while the regiment was in the field rather than on garrison duty), gunworms, pickers and brushes, leggings, spatterdashes, and rollers (another name for neck stocks). The dozen existing rolls cover the years of 1757 and 1758. The companies of captains Andrew Lewis, Joshua Lewis, Robert McKenzie, Thomas Waggener, and Henry Woodward are represented. Waggener’s company is over-represented with a total of seven necessary rolls surviving. It is interesting to note that only shirts, stocks, stockings, and shoes are issued in quantities greater than one to each soldier.

Figure 8 This is an example of one of the size rolls in the George Washington papers on microfilm in the Library of Congress. Items listed here are pretty standard throughout the dozen entries in the papers. The last entry of this particular one (for Robert McKenzie’s company for March 1758) has a final entry of two items, powderhorns and shot bags, in the last box. These were used by the regiment because of the frequent condition of cartridge paper being in short supply. Note that item #3 lists cartridge (cartouch [sic]) boxes. All size rolls consistently list combs (item #15 here). The author believes these combs may not be for grooming but for hair style as mentioned in Cuthburtson (78), although it is acknowledged that regular hair care may be a purpose (Cuthbertson, 79). The roll reads at the top: "A necessary Roll of Capt. McKenzies Company for March 1758". The items in each box are as follows: guns (frequently referred to in other rolls as "firelocks"), bayonets, cartouche boxes, belts and frogs, coats, waistcoats, breeches, hats, shirts, shoes, stockings, stocks (neckstocks), blankets, cockades, combs, garters and buckles, shoe buckles, knee buckles, canteens, haversack, knapsack, and powder horns/shot pouches. The neckstock may have been of black leather in 1757 if the private men were equipped the same as the officers (Abbot, v. 4, 373). Frequently occurring items appearing on other necessary rolls are cartridges, swords, and sashes. It is of note that from the listing of cartridges, it is apparent that in 1757 boxes holding twelve cartridges were used, while in 1758 the smaller nine-cartridge box was used. The swords and sashes are consistently issued to the sergeants of the companies.

Summary

This is not a definitive report concerning the clothing and equipment of the Virginia Regiment, but merely a report on the state of research thus far uncovered. It is hoped that furture research in English and Canadian repositories may yield more detailed information.

The regiment exhibited some variation around the accepted clothing and equipment requirements of an English army of 1750-60. Availability appears to be the most significant variable effecting clothing and equipment choices while expense appears to be a close second. The uniform appears to be more haphazard in the early years as the colony was struggling to adjust to a wartime situation. Beginning in 1757, it seems that the colony had learned how to deal with many shortages and had developed the contacts to enable the colony to acquire what it needed, though not always in a timely manner. Thus we see a regiment half uniformed in 1754, meagerly uniformed in 1755, having to wear the same uniform a second year (by the end of the time, most of the uniforms had likely been reduced to rags and discarded), and getting its first bonafide uniform in 1757 and apparently uniformed on a somewhat yearly basis with high quality uniforms thereafter. After the first year, the regimental colors of blue with red facings were adopted for the uniform; a color scheme that the regiment would use until its disbandment in 1762.

Bibliography

Abbot, W.W., ed. The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series. Charlottesville: The University Press of Virginia, 1983-95, 10 vols.

_______ Annual Register. London: R. and J. Dodsley, 1761.

Brock, R. A., ed. The Official Records of Robert Dinwiddie, Lieutenant-Governor of the Colony of Virginia, 1751-1758. New York: AMS Press, 1971 (reprint), 2 vols.

Cuthbertson, Bennett. A System for the Complete Interior Management and Oeconomy of a Battalion of Infantry, 2nd ed. London: J. Millan, 1779.

Franklin, Benjamin. The Pennsylvania Gazette. Philadelphia

Titus, James. The Old Dominion At War: Society, Politics, and Warfare in Late Colonial Virginia. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1991.

Washington, George. The Papers of George Washington. Washington D.C.: The Library of Congress (microfilm), series 4. General Correspondence, 1697-1799.

Illustration Credits

Jacobs, Wilbur R. Wilderness Politics and Indian Gifts: The Northern Colonial Frontier, 1748-1763. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1950. Figure 7

May, Robin. Wolfe’s Army. London: Osprey Publishing, 1974. Figures 3-5.

Miller, A. E. Haswell and N. P. Dawney. Military Drawings and Paintings in the Royal Collection, v.1. London: Phaidon Press, 1966. Figure 2.

Russell, Francis. The French and Indian Wars. New York: American Heritage Publishing Co., 1962. Figure 6.

Library of Congress microfilm collection of the George Washington Papers , Necessary Rolls, series 4. Figure 8