©2000 Terry Gruber

HAMPSHIRE COUNTY CRISIS: APRIL 1756

The coming of spring to Hampshire County in 1756 brought renewed anxiety to the county residents. The memory of the Indian raids throughout the region the previous summer and fall created a sense of urgency in this spring’s activity. An urgency not centered on normal seasonal planting activities, but on defense and survival. Neither the colony or the Crown appeared to be in a position to provide full protection for the frontier inhabitants. Dreadful anticipation of renewed Native depredations occupied the backs of settlers’ minds. Another round of raids threatened to release a panic that might depopulate the Virginia backcountry before any authorities could realize what happened.

The defeat of General Edward Braddock's force near the Forks of the Ohio the previous summer had left the Virginia frontier nearly defenseless. The victory by the combined French and Indian force had destabilized Virginia’s frontier. For the first time in decades of conflict between the English and French in North America, the Virginia frontier was endangered. Only a few weeks passed before the Indian allies of the French began their relentless, devastating attacks on the citizens of Hampshire County. The outermost defense remaining after Braddock’s defeat was Fort Cumberland, but the forces to defend the backcountry were far too small. Developing a defensive strategy, therefore, occupied the thoughts of the provincial military authorities.

By March of 1756, the colony completed two forts on Patterson Creek and reorganized its military forces. George Washington was commissioned colonel of the Virginia Regiment. Recruiting continued, but thus far fell far short of the 1000 men anticipated. The first round of Indian attacks for the year, beginning around April 1, showed the colony how unprepared it was to meet the challenges of war. The French and Indians arrived with renewed fury. For one month, chaos ruled the frontier.

The first hint of the coming storm was in a letter from Lieutenant Colonel Adam Stephen, who was in command of the Virginia forces at Fort Cumberland. As a postscript to a letter, dated 29 March 1756, Stephen reported to Colonel Washington that they had been "much harassed by the Indians" on several recent scouting parties.1

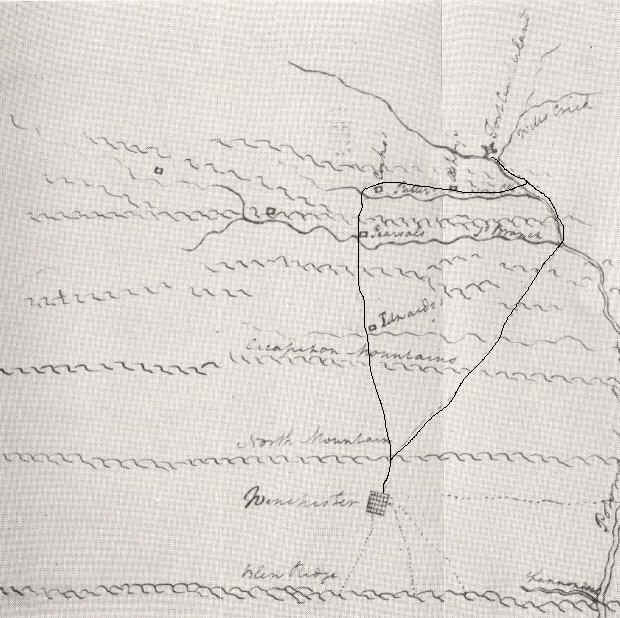

Figure 1 This is a sketch made by George Washington in 1758. It shows the defenses of Virginia's northern Frontier. The roads have been enhanced that lead from Winchester to Fort Cumberland (shown as a star-shaped symbol on the top right). The wagon road to the South Branch contains square symbols that represent Forts Edwards, Pearsal, Cocks, and Ashby. The two boxes to the south (left) are Forts Pleasant and Defiance, respectively.

Between March 29 and April 1 more reports of trouble were sent to Williamsburg. When Washington arrived in Williamsburg on April 1 from a meeting in Massachusetts, the Speaker of the House, John Robinson, suggested that Washington hurry to Fort Cumberland. Washington left immediately, arriving in Winchester on April 6.

The next day Washington reported to Governor Robert Dinwiddie that a skirmish had occurred recently between 23 men of the Frederick County militia and approximately 15 Indians on North River. After about 30 minutes of fighting, the Indians fled the battleground, leaving several of their dead. Among the dead was the commander of the detachment, Ensign Alexandre d'Agneau Douville. Recovered from the ensign's body were the orders from the commandant of Fort Duquesne. Douville's party was ordered to gather information, cause what trouble it could and, if possible, blow up the supply depot at the mouth of the Shenandoah Valley. This was alarming news. It meant that hundreds of Indians could be on their way to Virginia.2

Figure

2 Robert Dinwiddie, Lieutenant-Governor of Virginia, 1751-58.

Figure

2 Robert Dinwiddie, Lieutenant-Governor of Virginia, 1751-58.

Washington immediately sent out orders to prepare for the coming storm. He ordered Lieutenant John Blagg and 20 men to rush to Joseph Edwards's on the Cacapon River to keep the inhabitants in place, offer assistance, and maintain the communication between Edwards's and Enoch's fort located at the forks of the Cacapon River. Orders were sent to Stephen at Fort Cumberland to send a detachment of between 100 to 150 men to Enoch's in order to rendezvous with Washington and a militia force he was attempting to collect. However, by April 12 the militia had not materialized, so Washington ordered the Fort Cumberland detachment, under Captain John Fenton Mercer, to proceed to Edwards's.

On the April 15, a sergeant and 10 men left Winchester with a supply wagon and orders for Mercer. While the wagon was enroute, Captain John Ashby was having a parlay with an attacking force of over 100 warriors which had surrounded Fort Ashby. Ashby refused to surrender, so the Indians withdrew in the evening and attacked a small supply post at the mouth of Patterson Creek. The post withstood the attack.3

The supply wagon and dispatch to Mercer arrived the night of the 16th. Mercer was ordered to leave a skeleton crew at Edwards's and go down the Cacapon to Enoch's fort. From there he was to engage Henry Enoch as a guide and proceed to Warm Springs Mountain to investigate reports that Indians were encamped there with some captives. The next morning, Mercer attempted to carry out his orders, but had to turn back. He was unable to cross North River because heavy rains the night before had caused the river to rise 8 feet. This was the last report Washington would receive from Mercer.

Figure

3 French attacking a fort.

Figure

3 French attacking a fort.

The next evening, the 18th, Lieutenant William Stark sent a dispatch to Washington in Winchester telling of a disaster which occurred a short distance from Edwards's. Three men of the regiment were within sight of the fort checking on the horses, when they spied a party of Indians. They rushed back to the fort to alarm the garrison. A party of about 50 soldiers, led by Mercer, was immediately dispatched. They pursued the Indians one and one-half miles when, as they began the ascent of a mountain, a larger adversarial force opened fire. After a thirty minute fight, the Virginians were surrounded and forced to make a hasty retreat. Among their losses were fifteen private men, Ensign Thomas Carter, and Captain Mercer. Stark reported the number of attackers as "upwards of an hundred". The sergeant delivering the dispatch added that the fort was surrounded, they expected an attack the next day (which never came, the enemy apparently had withdrawn during the night), there were many French among the attacking force, and a large part of the party was mounted. The backcountry entered into a state of panic.4

During the next three days, Washington tried to allay the general feeling of impending disaster. Reinforcements and supplies were sent to Edwards's and instructions to keep open the communication between there and Ensign Edward Hubbard's tiny force at Enoch's. Each fort in Hampshire County was quickly becoming a tiny island in a raging sea of French and Indians. Once completely isolated, these forts would likely be forced to surrender.

Figure

4 Shawnee scout.

Figure

4 Shawnee scout.

By the 21st, the situation was desperate. The inhabitants of Hampshire County fled, along with those of Frederick County, to the area east of the Blue Ridge. Some settlers considered negotiating favorable terms of surrender with the enemy, an act Washington considered not worthy of British subjects.5 Daily reports of murders poured into the military command at Winchester. All communication between the forts was severed. Winchester was not yet isolated, but was dangerously close to being so. Worse yet, there was little encouraging word from Williamsburg for a timely relief force.

The tremendous strain of these events began to press unbearably on Washington's spirit. The 24 year-old began a letter to Dinwiddie, dated the 22nd:

I am too little acquainted, Sir, with pathetic language to attempt a description of the peoples distresses . . . But what can I do? . . . The supplicating tears of the women; and moving petitions from the men, mealt me into such deadly sorrow . . . I see inevitable destruction in so clear a light, that [unless help soon comes] the poor Inhabitants that are now in the Forts, must unavoidably fall .6 . .

He continued the letter, saying that three days of trying to raise the militia from the surrounding counties had produced only 20 men. It was impossible to attempt to drive out the enemy because the regiment was dispersed into small parties for the protection of the inhabitants.

The next day, a Council of War decided that Hubbard must evacuate and burn Enoch's fort, then join the force at Edwards's, now under command of Captain Henry Harrison. From there, Harrison was to remove all but a few soldiers, any inhabitants that were with him, and their livestock, and proceed to Winchester. Three days later, as Harrison was leaving Edwards's, Washington requested him, while passing Darby McKeever's place on the Cacapon River, to stop there and bury McKeever and several of his neighbors. By this time, no one was living in Hampshire County except a couple of families at Edwards's and at a few settlements around Fort Pleasant in the middle South Branch valley.

While the Council of War was being held in Winchester, Captain Thomas Waggener, his men, and settlers around the upper Trough area were becoming invloved in their own crisis. A letter from Fort Hopewell to the County Lieutenant, Thomas Bryan Martin, described the events which later became known as the Battle of The Trough.7

A contingent of militia from Fort Hopewell had left the fort in search of some French and Indians reported in the neighborhood. When advancing into The Trough, they were caught in an ambush. The enemy fired down upon them from the steep slope of the mountain. The flooded South Branch severely limited their choices for escape and many lost their lives. Fort Hopewell, located on the east bank of the South Branch a few miles south of Fort Pleasant, came under attack by the recently victorious force of Indians and French. Being unsuccessful in capturing the fort, they withdrew.

Waggener and his men could hear the gunfire coming from the direction of Hopewell, but the heavy rains of the past week caused the South Branch to be an effective barrier against a relief force for the unlucky Hopewell inmates. The next day, they were able to cross the river to assist the Hopewell garrison in a pursuit of the attackers. The combined forces of provincial and local forces were unsuccessful in locating the raiders.

Back in Williamsburg, the colonial government's reaction to the numerous reports of destruction was surprisingly swift. The first word of action was from Dinwiddie. In his letter to Washington dated April 15, he stated that he was in the process of convincing the Cherokees and Catawbas to come to the northern frontier to provide assistance. However, the anticipated force of 40 to 50 Indians dwindled to 13 Nottoways when they arrived at Fort Cumberland on May 18. Dinwiddie ordered, on April 26, the militias of Frederick, Fairfax, Prince William, Culpepper, Orange, Stafford, Spotsylvania, Caroline, Albemarle, and Louisa Counties to assemble in Winchester. These forces began to arrive in Winchester on April 29. By May 2, over 100 men of these militias were present. However, by this time numerous reports stated that the Indians had returned to Fort Duquesne. The crisis was over.8

During the last half of April, the assembly drafted a bill to authorize an increase in the manpower of the regiment by one-fourth. The same bill authorized funds to construct a chain of forts stretching some four hundred miles from the Cacapon River to the Mayo River in Halifax County. The bill was signed on May 1 by Governor Dinwiddie, too late to be of service for this crisis.

This was just the beginning of a series of raids that Hampshire Countians would have to endure every year until Fort Duquesne finally was captured by a combined Crown and provincial force. Yet, out of this first crisis of the year came long-term benefits. The Assembly committed the resources of the colony to protect the frontier inhabitants for the duration of the French and Indian War. Although Hampshire Countians could not be promised a reasonable measure of safety until Fort Duquesne fell in November of 1758, the colony's efforts did encourage many to stay and endure the hazards of frontier living.

Endnotes

1GW Papers 2:325.

2Ibid., 334-337. This skirmish may have occurred in the vicinity of Thomas Parker’s fort on North River in present North River Mills, Hampshire County. However, there is no conclusive documentation about the precise location the confrontation took place. 3Ibid., 3:23, n. 2. 4The Fort Edwards battle details can be found in GW Papers 3:17-18 letter from William Stark, 3:19 letter to Thomas Lord Fairfax, 3:20 letter to Robert Dinwiddie, 3:72-4 Court Martial, and 3:77-9 Court Martial. Although Kercheval mentions the battle in his book, most of the account is rather confused and unreconcileable to the above primary source material.5The rather treasonous behavior is reported by GW to Robert Dinwiddie on 24 April 1756 in GW Papers 3:46. It is also reported that the leaders of this surrender faction were jailed, see ibid., 47, note 7.

6Ibid., 33 7The following description of the Battle of The Trough is taken from both Kercheval, 73-4 and GW Papers 3:46. Although the GW Papers do not identify the event as the Battle of The Trough, the timing and certain descriptions in the GW Papers match enough of the Kercheval story to deduce both stories describe the same event. Martin was a nephew of Lord Fairfax and served as his land agent for the lands in Frederick and Hampshire Counties in addition to his duties as County Lieutenant, or head of the county militia. The Trough is a narrow defile of several miles long cut by the South Branch of the Potomac as it passes between two mountains. Fort Pleasant is located at the upper end of The Trough. Fort Hopewell may have been a more formal name for Town Fort. If Hopewell was indeed Town Fort, then the fort would be located about three miles upstream from Fort Pleasant. 8Dinwiddie’s report of Indian aid is in GW Papers 2:356. Dinwiddie’s orders to call the militia are in ibid., 3:55. The return of the Indians to Fort Duquesne is reported in a May 3 letter to Dinwiddie by GW in ibid., 3:82. Around April 23, the party that attacked Fort Edwards and Fort Ashby was attacked while returning to Fort Duquesne near the Savage River in western Maryland (reported in the Pennsylvania Gazette 27 May 1756 issue).

Bibliography

Abbot, W. W. ed. The Papers of George Washington: Colonial Series, 10 vols. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983-97.

Brock, R. A. ed. The Official Records of Robert Dinwiddie, 2 vols. New York: AMS Press, 1971 (reprint of Virginia Historical Society, 1883).

Kercheval, Samuel. A History of the Valley of Virginia. Woodstock, Va.: W. N. Grabill, 1902 (originally published 1833).

Pennsylvania Gazette, 27 May 1756, Accessible Archives, Item #19556, http://accessible.palinet.org/cgi-bin/accessible/verify.pl .

Titus, James. The Old Dominion At War: Society, Politics, and Warfare in Late Colonial Virginia. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1991.