©1998 Terry Gruber

Ashby’s Fort: Defending the Colonial Frontier

"The plantation of Paterson’s Creek is entirely ruined…the smoke of the ruined houses is so great as to hide the adjacent mountains, and obscure the day."

The Gentlemen’s Magazine, London, January 1756

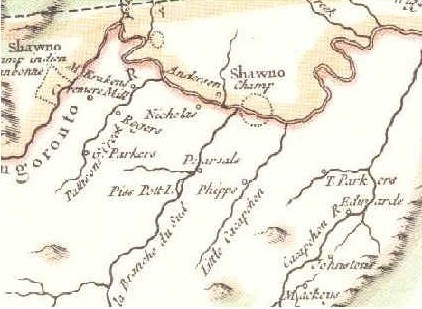

The Patterson Creek valley was devastated during the late summer and early fall of 1755. The defeat of Braddock’s force at the hands of the French and their Indian allies at the Forks-of-the-Ohio in early July had left the Virginia frontier at the mercy of marauding bands of hostile Indians. Although there were some troops stationed at Fort Cumberland to provide some measure of protection, they were too few and too demoralized to provide any protection beyond the safe walls of the Crown fort at Will’s Creek. Consequently, the Virginia northern frontier was a ripe fruit that needed only to be plucked, unless the colony took quick defensive measures.

Within a few weeks after the Braddock defeat, two companies of rangers were authorized to serve in Frederick and Hampshire Counties. William Cocks and John Ashby were appointed to command the 1st and 2nd Companies of Rangers, respectively. Both men were given captain’s commissions. By September 1755 both companies, with approximately 30 men each, were patrolling the area around Patterson Creek.

With the approach of cold weather, the new commander of the Virginia Regiment, George Washington, ordered Lt. John Bacon of the Maryland forces to leave Fort Cumberland to oversee construction of two forts on Patterson Creek to house the ranger companies. By December, both forts were completed and garrisoned by the rangers. The 2nd company, commanded by Captain Ashby, was stationed at the fort built "…at the Plantation of Charles Sellars, or the late McCrackins…"1 now located in Fort Ashby, Mineral County, West Virginia. From the moment of its occupation until its demise, the fort took the name of its first commander; it was referred to as Ashby’s Fort.

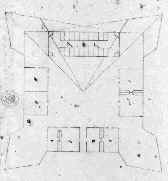

The fort had a square stockade of 90 feet made of upright logs. Stockades on frontier forts were typically 12-15 feet high. Projecting outward from all four corners of the stockade were bastions; half-diamond shaped structures that were designed as the primary defensive points in forts of this period. The projecting bastions were also necessary to prevent an enemy from seeking cover at the stockaded walls of the fort (called curtains), thereby enabling an attacker, with relative safety, to breach the wall. These bastions were constructed of "hewn logs" and were probably of a strong, double-walled, earth-filled design. Inside the fort, a barracks and magazine were instructed to be built.2

Although initially intended to protect the inhabitants of Patterson Creek, by the time of its occupancy by the 2nd company, the valley was virtually abandoned. Instead, the fort served to protect the supply line between Fort Loudoun in Winchester, Virginia and Fort Cumberland.

The spring of 1756 proved to be an extremely eventful period. Fort Ashby experienced the opening engagement of a month-long reign of terror. In a dispatch of 15 April 1756 sent to Fort Edwards on the Cacapon River, Ashby described an attempt of "a vast number" of Indians to persuade him to surrender or die. The captain, apparently knowing his men would be safe within the fort, dared the force to attack him. Being unsuccessful in their attempt to bluff the garrison out of the fort, the attackers moved elsewhere that evening. This large attacking force may have been the one that inflicted a disastrous defeat on the Virginia Regiment forces stationed at Edwards’s Fort three days later.3

Another event, occurring around July 25 of the same year, did not end with such exemplary behavior. Lt. Thomas Rutherford, now in command of the rangers at Ashby’s (Ashby having retired as the ranger companies were being disbanded), a few of the remaining rangers, and a number of militia were escorting an express from Winchester to Fort Cumberland. Some of the flankers spied some Indians in the woods ahead. When the alarm was sounded, the militia ran off before any firing began, leaving Rutherford and the ranger remnants no other choice but to return to the fort with the panicked militia. No mention is made of the party of Indians, so it can be assumed they went elsewhere.4

The disastrous April 1756 induced the legislature to take more seriously the attacks that were taking place in the backcountry of the colony. In May, the House of Burgesses approved the funding to erect a "chain of forts" that would stretch from the Potomac to the Mayo River, a span of nearly 500 miles. Ashby’s Fort was made a part of the defensive chain.

In early 1757, Fort Ashby was abandoned by the Virginia Regiment. The absence of inhabitants to protect together with a reduction in size of the Virginia Regiment and the loss of several hundred from the frontiers to act with the British in South Carolina contributed to the decision to abandon the fort. Not until the spring of 1758 was a garrison stationed at Ashby’s.

The arrival of the British forces at Raystown (later Bedford, PA) signaled a renewal of activity at the fort. Ashby’s was garrisoned again to protect the supplies and dispatches that moved along the road between Winchester and Fort Cumberland. Traffic on the road reached a peak during the summer and fall as the campaign to capture Fort Duquesne at the Forks-of-the-Ohio made its way through western Pennsylvania and began to draw supplies from western Virginia. After the conclusion of this successful campaign, the region was stabilized, making transportation and habitation much safer. Fort Ashby was not an essential element any longer and may have been used only intermittently until the end of hostilities in 1764, when it was, in all likelihood, abandoned. All that remains today of the fort is the barracks; the portion of the fort now identified as "Fort Ashby".

One last note: Fort Ashby served as a brief training ground for a future general and heroic icon of the American Revolutionary War. Daniel Morgan served as a private in Ashby’s company and spent his brief 10-month military career of the French and Indian War at Ashby’s Fort. While on duty with the ranger company, he received his first wound while escorting an express from Ashby’s to Winchester.5

Footnotes

1Quote in GW Papers, 2:137 in letter to John Bacon. 2ibid 3GW Papers 3:23-4, n. 2 4GW Papers 3:313, letter to Robert Dinwiddie 4 August 1756. More detail is given in a letter from Adam Stephen 25 July 1756 in 3:294-5.5Morgan is listed on "Weekly Return of the 2nd Co. Of Rangers Stationed at Sellars’s:Plantation on Pattersons Creek under Command of Capn John Ashby 29 Dec 1755", in the Library of Congress GW Papers. The incident of Morgan’s wound is described in a letter from Captain John Fenton Mercer to GW dated 17 April 1756 in GW Papers 3:11.

Bibliography

Abbot, W.W., ed. The Papers of George Washington: Colonial Series, 10 vols. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983-1995.

Cocks, William. "Journal" in The George Washington Papers, Library of Congress microfilm.

Reese, George, ed. The Official Papers of Francis Fauquier, Lieutenant Governor of Virginia, 1758-1768. 3 vols. Charlottesville: The University Press of Virginia, 1983.

Stevens, S. K., Donald H. Kent et al, ed. The Papers of Henry Bouquet, 5 vols. Harrisburg: The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1951-1994.

Titus, James. The Old Dominion At War: Society, Politics, and Warfare in Late Colonial Virginia. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1991.

Waddell, Louis M. and Bruce D. Bomberger. The French and Indian War in Pennsylvania, 1753-1763: Fortification and Struggle During the War for Empire. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1996.

Washington, George. The George Washington Papers, series 4, reel 29, Library of Congress microfilm.